“Why are we here? Where do we come from? Traditionally, these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead,” declared prize winning physicists Stephen Hawking. “Philosophers have not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics,” he added, “Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.”

Hawking’s address on philosophy was undoubtedly a bold declaration of the inadequacy of philosophers in general. And Hawking’s statement has its merits; for millennia, philosophers had relied on metaphysical principles to arrive at conclusions. And admittedly, certain philosophers today are uninformed of the most up-to-date scientific research to support or refute their stance. But perhaps Hawking’s mindset is best explained by his contemporary Neil deGrasse Tyson, as he said, “All of a sudden [philosophy] devolves into a discussion of the definition of words… The scientist says, ‘Look, I got all this world of unknown out there. I’m moving on… You can’t even cross the street because you are distracted by what you are sure are deep questions you’ve asked yourself.’” Even Bill Nye the Science Guy has seemed to adopt a similar attitude, as he answered on BigThink, “Philosophy is important for a while, but… you might start to argue in circles.”

With the popularity of the three scientific giants, many young scientists had followed their attitude towards philosophy. Students studying in bachelor or even graduate science degrees might be required to take a philosophy course as a graduation requirement but dismiss the philosophical knowledge learned. Despite the rise in popularity of such an attitude, it should not distract us from critiquing a suicidal blow of “Philosophy is dead.” To borrow George Orwell’s language, Hawking and his contemporaries might have a disdain towards the study of philosophy, but the view that “Philosophy is dead” is itself a philosophical attitude. In declaring the death of philosophy, Hawking had refuted himself. Philosophy is alive and well, but, unfortunately, contemporary scientists are too distracted by their quest to understand the material world and have forgotten metaphysical principles that gave birth to their fields.

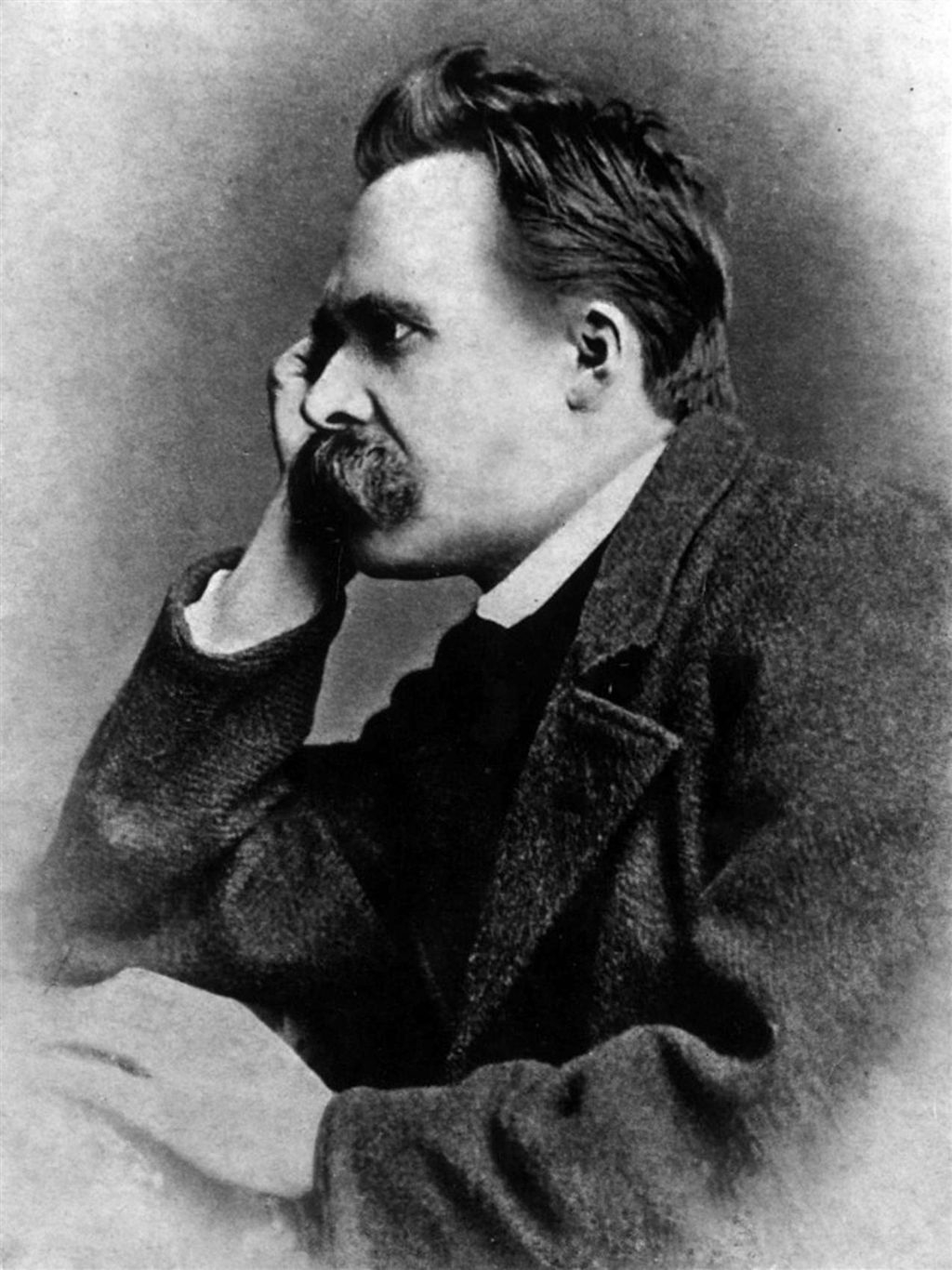

But this attitude towards philosophy among contemporary scientists should also bring us back about 200 years to the German philosopher Fredrick Nietzsche. He made a similar statement in his books The Gay Science and Thus Spoke Zarathrustra, “God is dead, and we have killed Him.” And this is perhaps Nitzche’s most infamously misunderstood statement, as many have viewed it to prescribe the necessary end of religiosity due to the enlightenment of human modernity. Even though Nietzsche was an atheist, he never used this statement to justify his beliefs in the lack of God. In contrast, Nietzsche’s “Death of God” was an observation of the effects of modernity - people living godless lives in the comfort of new scientific discoveries and inventions. Some commentators would even say Nietzsche’s infamous statement brought a hint of criticism towards people’s godless lifestyle since modernity had brought obscurity to objective morality and objective beliefs.

Despite the similarities in sentence structure, it should be evident by now that Hawking’s and Nietzche’s sentiments are fundamentally different. Hawking was making a factual declaration while Nietzche was making a cultural observation. Hawking and his contemporaries had dismissed the maternal figure of science and had strayed into ignorance, thinking that science, the child of philosophy, can replace the role of his mother. And contemporary scientists have ironically confirmed Nietzche’s observation, even though we are 200 years apart; modern scientists have taken the scientific method for granted but never made an effort to understand its epistemology.

Hawking’s philosophical attitude should prompt us to observe that philosophy is dead, and we have killed her, not because she is irrelevant, but because we are ignorant to acknowledge her forbearance to science. Scientists might have become the “the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge,” but they cannot do it without philosophy. Some philosophers might be asking deep questions and not crossing the road, but these are questions that assess how dangerous the road is before crossing. Philosophers might be asking curricular questions on unprovable assumptions, but so are the axioms of the scientific method. And to better mature this great field of study, scientists should be more aware of the metaphysics that gave birth to its methods and apply it in their observations.